Steven Ritz-Barr's chapter on filming 'Quixote' for the book 'Don Quixote: The Re-accentuation of the World’s Greatest Literary Hero'

To acquire the mood and the emotion of a scene, an abundance of words was used to convey the multi-level concepts within this work. Yet, in order for a puppet story to work, the fewer the words, the better. Too many words in the mouth of a puppet character can kill the puppet. In order for the puppet to “work,” it must convince the spectator to not only believe the words but also the actions of the performance. This concept is called the suspension of disbelief; it is like a spell. That spell is easily broken by too many words in the puppet’s mouth. If the spell is perceived by the spectator, or more exactly, if the techniques used to create the spell are discerned by the audience, then the puppet loses the ability to communicate the story’s emotional core. Needless to say, I did not want this to happen.

What is Puppetry?

At the heart of puppetry is Believing, or more rightly, suspending one’s disbelief for long enough to listen and believe. It is difficult enough to believe a flesh and blood actor, because we know he is pretending, but, paradoxically, it can be easier to believe a puppet due to its lack of pretention and the neutrality of the character.

A puppet is materially an object. The job of the Puppeteer is to allow the viewer to see a “living” character. When we look at an actual human face, we use a part of our brain called the fusiform gyrus. It is an oddly sophisticated piece of brain software that allows humans to distinguish among literally thousands of faces that we know. (Picture in your mind the face of Abe Lincoln. You just used your fusiform gyrus.) When we look at an object, however, we use a different and less powerful part of the brain, the inferior temporal gyrus, usually reserved only for object recognition.

It takes a talented artist to trick people into seeing a human face when they know it is an object. When this trick is achieved, the emotional impact of the message can be very potent. The human actor is recognized as a real human being and, as such, benefits from the empathy of the audience. The puppet designers, makers, and operators must work very hard to achieve the same empathy usually reserved for humans and animals. When they achieve it and evoke real emotions in the audience member, the message can be more powerful than if it was conveyed by human actors because of the energy the audience has invested in making the characters come alive. Puppets “live” only in the imagination of the viewer.

Human actors often add affectation to their interpretations. This can be called over-acting. It can hurt the integrity of the character the author created. Affectation is defined as non-authentic or unnecessary movements added by the actor to his character that display attributes of his own personality rather than the character he is portraying. It is noted that, “For affectation is seen, as you know, when the soul, or moving force, appears at some point other than the center of gravity of the movement. Because the operator controls with his wire or thread only this center, the attached limbs are just what they should be… lifeless, pure pendulums, governed only by the law of gravity.”

Don Quixote Adapted into a Puppet Film

by Steven Ritz-Barr

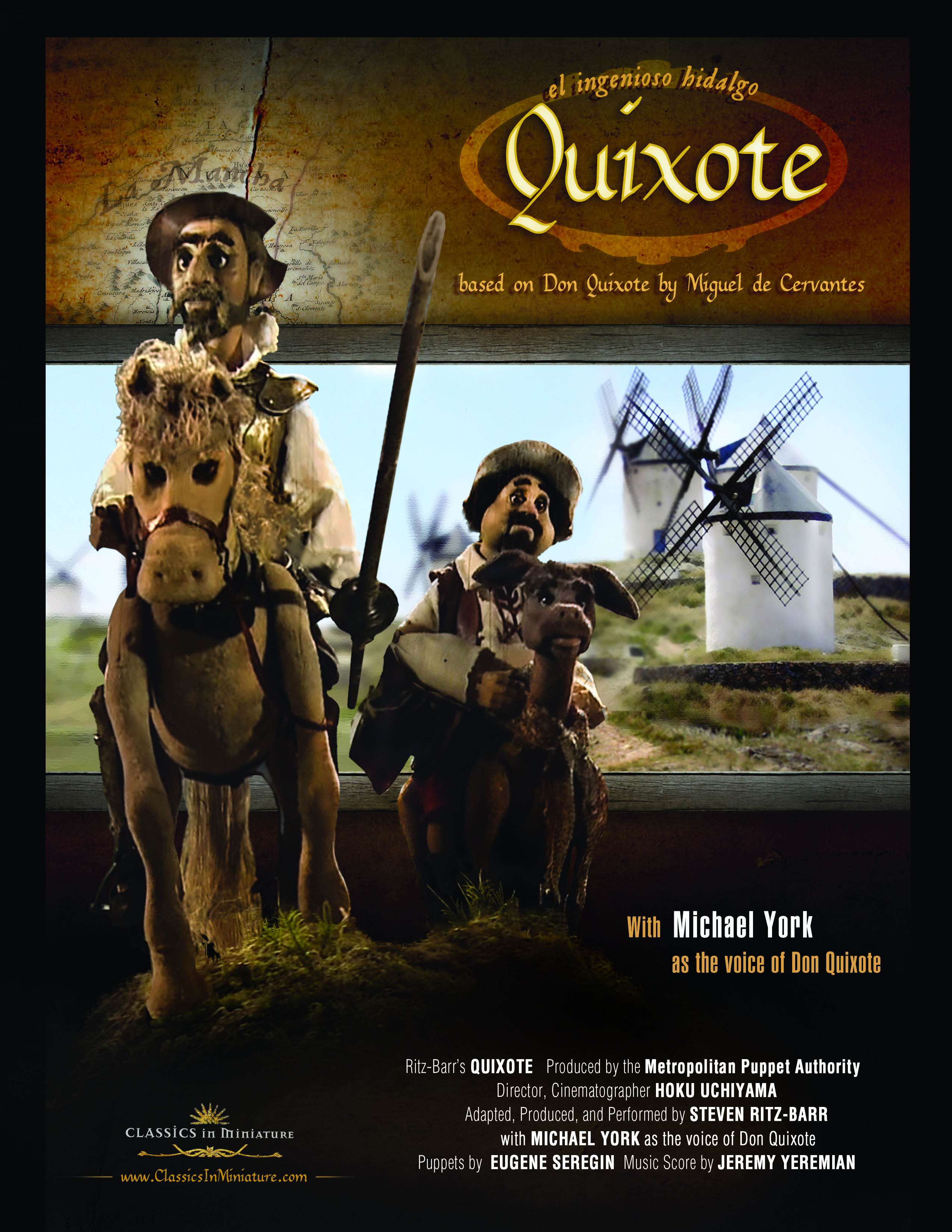

“Quixote” by Cervantes is the second film of a series called “Classics in Miniature.” Filmed in 2011, the goal was to develop a story that would allow for the use of string puppets as the characters in a live-action animated film. Transforming this voluminous book into a 30-minute film while retaining the integrity of the story was a challenge. I began by choosing parts that resonated personally with me, but I also chose scenes that best appealed to the limitations and advantages of puppet-film making. Our goal was to create a living, moving Don Quixote in the minds of the viewers, through a film to be watched and enjoyed by young viewers and adults, by educated and not-so-highly educated people alike. Our version had to be an entity in itself, meaning it must contain story background, generate some dynamic build-up, and have a conclusive finale in order for the film to stand on its own.

At the time this project began, I had just finished a two-year affair with Faust I by Goethe, which resulted in a 20-minute film with puppets without dialogue, the first puppet film of my own invention. The dark content of Faust made it difficult to continue with Faust II as previously planned. I needed a new direction. After reading Don Quixote, I knew that I would enjoy basking in Cervantes’ fictional world for the time it took to make a good film, specifically two years. But, coming up with a script tailored to a 30-minute marionette film was no small task. Should I adapt it to make it more contemporary? Which scenes should I choose to focus upon? How much should I rely on verbal rather than non-verbal communication? Other questions revolved around the success of the book and the fact that so many film versions (including some animated versions) had already been made previously. Why do another?

The puppet’s movements start at the center of the puppet and not in its limbs. It is not the foot moving forward or the hand reaching that drags the body behind it, but rather the movement starts from the center and thereby the limb movement follows the center and creates the illusion of unity in movement. It makes the puppet come alive with one force that moves it and not separate limbs going off in different directions. It is what gives a string puppet the uncanny feeling that it is indeed “alive.”

The main advantage with string puppets is a superb elegance of their movement. I chose realistic marionettes, proportioned and dressed like humans as my puppets. Since they resemble real people, they also had to move like real people to accomplish the illusion of life, unlike stylistic puppets such as Jim Henson’s Muppets or glove puppets like Mr. Punch. These marionettes’ main limitations are that they cannot easily grab, run, touch, or fight with their wooden, articulated arms and legs. In addition, it is almost impossible to change their clothes because the strings are sewn to their limbs through their clothes.

Heinrich Von Kleist tells a story in 1801 about an encounter he had with a friend concerning a string marionette performance he saw: “these marionettes, like fairies, use the earth only as a point of departure; they return to it only to renew the flight of their limbs with a momentary pause. We, on the other hand, need the earth: for rest, for repose from the effort of the dance; but this rest of ours is, in itself, obviously not dance; and we can do no better than disguise our moments of rest as much as possible.” In order to preserve the elegance of the movement of Don Quixote’s characters, I had to find scenes devoid of movements that are difficult for these puppets.

The Quixote puppets were made by Eugene Seregin, who learned his craft while working for 20 years for the legendary Russian Puppeteer Sergei Obrasov in Moscow, Russia before moving to Los Angeles. He became a master builder of marionettes over the years because he not only knows how to carve a character’s face, but he can also expertly engineer the controls to facilitate their operation. Don Quixote alone took four months to create. Mr. Seregin is one of few master marionette builders alive today with both the creative and technical vision to create elegant marionettes.

I read the book again, slowly.

I also discovered that a multitude of books had been written about this one book. I read a few of them, but the two books most inspiring to my work were Gustave Dore’s “Illustrations of Don Quixote” and Howard Mancing’s “The Cervantes Encyclopedia.” I never want to be overly influenced by the opinion of others, including experts, regarding a project, so I usually take their commentary lightly. I am not an academic. I did have some reservations concerning my film adaptation. My main thought was that there were simply too many words. This novel was written at a time (in 1608) when a new culture of street performance for commoners developed in 1570 in Italy had became known as the Commedia del Arte. This theatrical form relied primarily on gesture rather than dialogue. However, contrary to this verbal minimalism, books written at that time contained an abundance of words, often in the form of numerous tangential elements that blurred the plot. Don Quixote by Cervantes was no exception.

Limitations Inherent with Marionettes

Marionettes cannot easily come in close intimate proximity of each other because the controls for their strings above them collide, and the strings become entangled. One can change the visual perspective by putting one puppet ahead of the other, but this throws off the center of gravity.

So in the chapters I chose to adapt for my film I needed to avoid scenes that required tight close contact of characters. Furthermore, given their wooden and non-moveable fingers, the need for them to grab things or carry items had to be kept at a minimum. For example, the simple act of Don Quixote riding his horse required his hands to be holding the reins. They had to be glued to his hands and unglued when he talked or when he was not on his horse. The patience required for these small movements is phenomenal, and the actions must be prioritized in order to keep the momentum of a scene going while one is shooting it.

My Point of View

Throughout the book, Don Quixote blames his shortcomings, his mental lapses, on the “Enchanter.” However, I wasn’t sure whether Cervantes wanted his reading public to believe in this character as a real entity or not, i.e., to realize that it was a fiction of Don Quixote’s imagination. When I re-read the book, this diffusion of responsibility for all of his acts leading to pain and destruction in the name of knightly pursuits of the good began to gnaw at me. I understood that Cervantes’ character is a comedic invention, a Clown character of the highest order, a contrarian of human behavior, but did he always have to divert responsibility to this supernatural power of the Enchanter, in such an obvious manner? Yet, this lack of self-awareness seemed to remain a consistent element of his thinking throughout the book. He was simply not able to find fault in himself or flaws in his acts as a knightly savior.

For my film I needed a satisfying ending. Because of the short length of the film, I needed an ending other than his death. In order to allow for a story conclusion to exist, I decided to set up an emotional moment with the right character to deliver it. I figured that this story device, the messenger, had to be Sancho who was closest to Quixote and suffered with him through all adventures. He not only had become close to Quixote, but he accepted the kind of flights of fancy Quixote displayed without mocking him. Yet, it so happened that my messenger figure became Andreas, the beaten boy. He was the one character that could elicit sympathy because he personally suffered due to the delusions of Don Quixote. And he was almost a child.

But it meant I had to bring Andreas back to the inn to see the puppet show of Maesa Pedro. And of course this was a huge jump cut in my interpretation. (A jump cut is a film editor’s term for an abrupt passage of time.) After Quixote ransacked the puppet theater, he and Sancho were ousted from the performance. However, Andreas recognizes and follows Don Quixote and Sancho out of the inn at night. The confrontation between Andreas and Don Quixote is described in the book, but I added my own particular point of view to this interchange. Don Quixote is confronted for having not only added to but also caused Andreas’ long-term physical distress. Sancho and Don Quixote remember the boy and remember the details of their last meeting especially since Andreas is now wounded badly (in my film). Quixote makes no comment to Andreas, now a hapless wonderer who appears crippled, as he barks, “you are the Enchanter, Don Quixote.” The voice of Andreas in the film had become my own voice. In fact, I did the voice-over of this character myself in the final version of the film.

In my re-interpretation, after this scene in the dark forest, Quixote reassesses his quest for righteousness and decides to go home. Andreas’ remark is able to startle Quixote out of his madness and cause him to recognize the voice of the enchanter as possibly his own. Then, I finally allow him to connect with reality rather than to live only in his imagination. I decided to end my film by making Quixote aware of his surroundings. This conclusion allowed us to recap the film locations we used. It is dawn; he passes the sheep and sees them as sheep. He sees where he insisted that the merchants bow to the name of Dulcinea, and he sees the windmills as windmills. I freeze frame the final shot by twisting the cliché scene of the hero riding off into the sunset by having them ride off into a sunrise.

I decided that it was not necessary that the viewer witness the death of Don Quixote in this short film. The abbreviated length of the film would have made it too powerful a scene and too sad. It would not have been the relief that death grants the character in the book. When he finally dies, there is a certain relief because the reader recognizes not only that he is old and his wanderings are over but also that he is now free to move into a fully imaginary world. Death is a satisfying ending to the book.

The Setting and Scene Design

I saw the story as “an exploration of the place where our inner and outer worlds meet. Indeed, Cervantes’ narrative moves in two dimensions at once: within the hearts and minds of Don Quixote and Sancho and through the physical world they actually traverse. They are equally important.” Cervantes is meticulous in his realistic depictions of scenery. He describes inns, palaces, forests, trials and paths, rivers and mountains. The knight and his squire interact with many people throughout the novel, and it is in these interactions that their bond is forged.

The scene design we used for the backgrounds of sets had to communicate the illusion of vastness. We originally experimented with craft materials to make artful handmade backgrounds but settled on photos of real landscapes. Thus, our backgrounds were mostly photos from La Mancha landscapes projected onto a screen from behind the set. My wife had taken the photos while we were visiting Spain. We then only had to arrange the foreground elements to fit these rear-screen projections to give us these vast expanses of countryside. In fact, we discovered that we did not have all the necessary images for all the scenes, so some of the projected photos were taken later where I live in Topanga, California, near the ocean of Southern California. The chaparral looks surprising similar to that of La Mancha. Again, this was part of how I made this story and this film personal.

The Middle of the Film Script

I really wanted the book-burning scene in the film. After many attempts to do this, I inserted the event where Don Quixote hires Sancho Panza as his squire. I set up the book burning as a distraction for the two to escape the caring gaze of his aunt and his housekeeper. I wrote two montage sequences where both realities happen simultaneously. (A montage is a series of abbreviated sequences edited together.) The ambiguous reason Sancho had to hang around the house after he had delivered an injured Don Quixote was so that he would receive some reward for the services of bringing his neighbor home. So I had Quixote directly reward him with the outlandish promise of adventure and the Island as is in the book. I took great care to portray Alonzo’s maid and his niece as responsible family members who were trying to do their best to take care of him. But alas, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza escaped out the back door while the others were busy clearing out his library and causing it to go up in smoke. This represented the second part of the film.

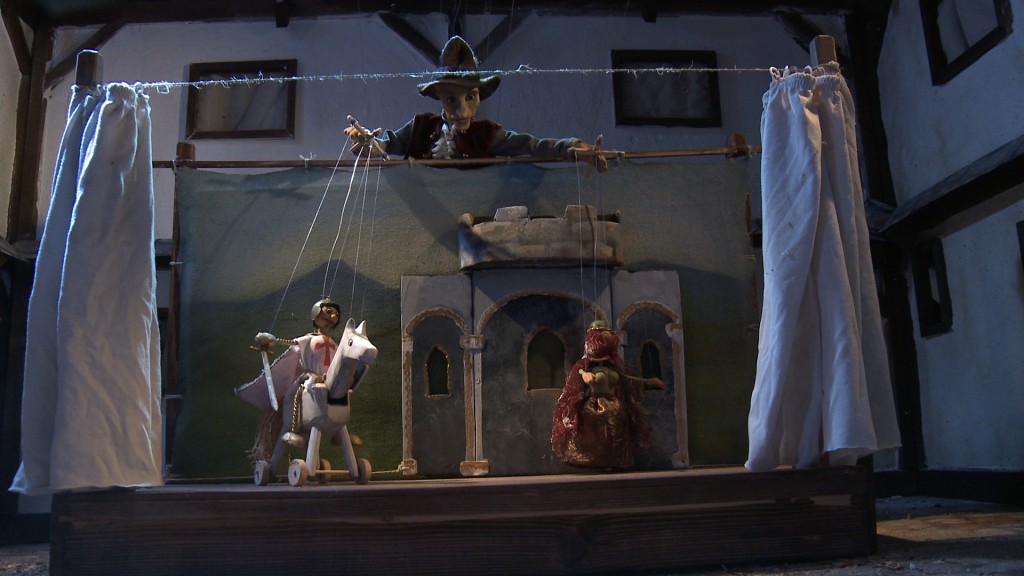

Finally, Don Quixote and Sancho were on the road. Here, I had hoped to be able to portray five or six important scenes with our two heroes but could only portray three events, due to my time constraints. The Windmill scene had to be there, because this iconic scene represents the most known episode in the novel to anyone who has ever heard of it. Second, the scene of the puppet theater of Maesa Pedro had to be there as an homage to puppet theatre in general. I have performed live puppet shows for many years before I made this film. Don Quixote as the heckler who believed the scene so much he was willing to help the main puppet character was a scene too precious for any puppeteer to pass up. The physical ‘double entendre’ of puppets performing a puppet play was certainly one of the highlights of the film. We just had to create Maesa Pedro’s puppets in a simpler style than what we were using with Don Quixote. While I adapted Maesa Pedro’s scene I imagined Cervantes laughing; it certainly had me laughing. Originally I had the Gaiferous and Melisande story blocked to shoot with the mini-puppets just like Cervantes wrote it. But, just before we began to shoot the film, I had the idea to include Cervantes’ own Savadraa story in Algeria, one of the episodic stories Cervantes includes in his novel. I could grossly simplify it and switch out the characters, which worked.

So I had one last scene left to portray of the adventures of our heroes together. I chose to include the sheep scene, where he thinks he attacks an oncoming army but he is really only attacking sheep. I wanted to show how the collateral damage done by the deeds of Don Quixote could amount in death. However, the absurdity of an armored hero attacking sheep had me laughing so hard when I read it that it made it into the film.

My logic was as follows: 1) Quixote hurts only himself in his mistaking the windmill for giants; 2) he hurts only animals in the sheep scene; 3) but he committed the greatest of sacrilege in the Maesa Pedro scene. By mistaking the puppet play as reality he breaks the imaginative spell that theater and art cast upon their audience. The spell ceases to exist when his physical blows destroy the illusion and flights of imagination that the play offers the audience members for a short while and hence the reprieve from their day to day lives.

I now had the blueprint for my interpretation of Don Quixote. However, there remained a rhythm problem; it didn’t flow correctly. All of the episodes were high action, which is good for puppets, but there lacked a scene of retrospection. So I included a short scene with Don Quixote and Sancho camping. I took several interchanges from the original book and dropped them into one campfire conversation. I wanted to show Sancho drinking and slowly becoming drunk while Don Quixote kept on talking in his own world. Yet, time constraints forced me to cut what I had written substantially. So, in the final version of the film, Sancho appears to be sleeping through the whole Quixote monologue. It worked.

The reality of time (real time) affects every part of the film making process especially with a film that relies on puppets. The puppets broke down a lot, repairs were made daily, and scenes had to be altered because a prop was not ready when we had to shoot the scene. Almost every scene was written to be longer than it ended up in the film. I had to make many of those decisions while shooting, when literary judgment is working in a very intuitive mode. Thus, many decisions to cut the script were made in the hope that the visual world we created would be sufficient to convey the messages.

The Ending of the Film Script

For the conclusion of our film script, I decided to just put Don Quixote going back through his three episodes after his confrontation with Andreas, the beaten boy, and riding off with Sancho into the sunrise of a new day (hopefully towards a sequel). After Andreas declares, “It is you, the Enchanter, Don Quixote,” we simply allowed this information to sink into Don Quixote’s mind. His gesture of recognition came because he turned around to head home. He didn’t need to say anything, but by turning around a response was clear. Andreas’ comment jolted him enough to see “Spain” and the beauty of the world around himself.

Many of the decisions after we began to shoot the film were made collectively. Our co-director, Hoku Uchiyama, kept wanting “one more take”; our art designer, Seb Chardon, wanted “more time” to finish everything he made (windmills included), and our editors could have used a few more passes to clarify parts they felt could be tighter. We did no re-shoots of any sequence or inserts because the project was out of time and out of money, and I was out of energy.

After the filming was complete and a rough version of the editing was done, we gave the footage to some actors, asking whether they would be interested in lending their voices to a puppet, Don Quixote. I approached several Hispanic actors, with no success. Through a friend I heard that Michael York, the English actor, might be interested. I emailed Mr. York the script and the filmed images that contained a vocal “scratch track” (meaning that the voices were voiced by myself and Hoku only as markers for the puppet’s mouth manipulation, never to be used as the final voices). Mr. York agreed to do it if I would consider changing a few words. The requested changes referred to the Maesa Pedro scene, when the mini-white knight escapes the black knight. In the script I had written, “the tsunami of love,” having taken complete modern liberty with Cervantes’ text. Mr. York pointed out that a tsunami would be a bit of a stretch for anyone to know about at that time in Spain, and he asked me to change it to “tornado.” I agreed to this, but during our recording session I had him say both lines. As it turned out, the tsunami line was much funnier in the mouths of those little puppets, and Mr. York thought so too; thus, historically correct or not, it stayed in the film.

In conclusion, my re-accentuating of this major literary work boils down to Don Quixote accepting his responsibility in the making of his madness. By producing a film with puppets, I was aware of the multitude of constraints that dictate how a story can be told. But most importantly, I picked scenes and moments that moved me the most in the novel. I made this work personal. I had to adapt and make changes to the story while creating visuals that could transport the spectator toward what I thought was essential in the spirit of the book. We may have altered many parts from the original, but we hope we kept faithful to the essential core.